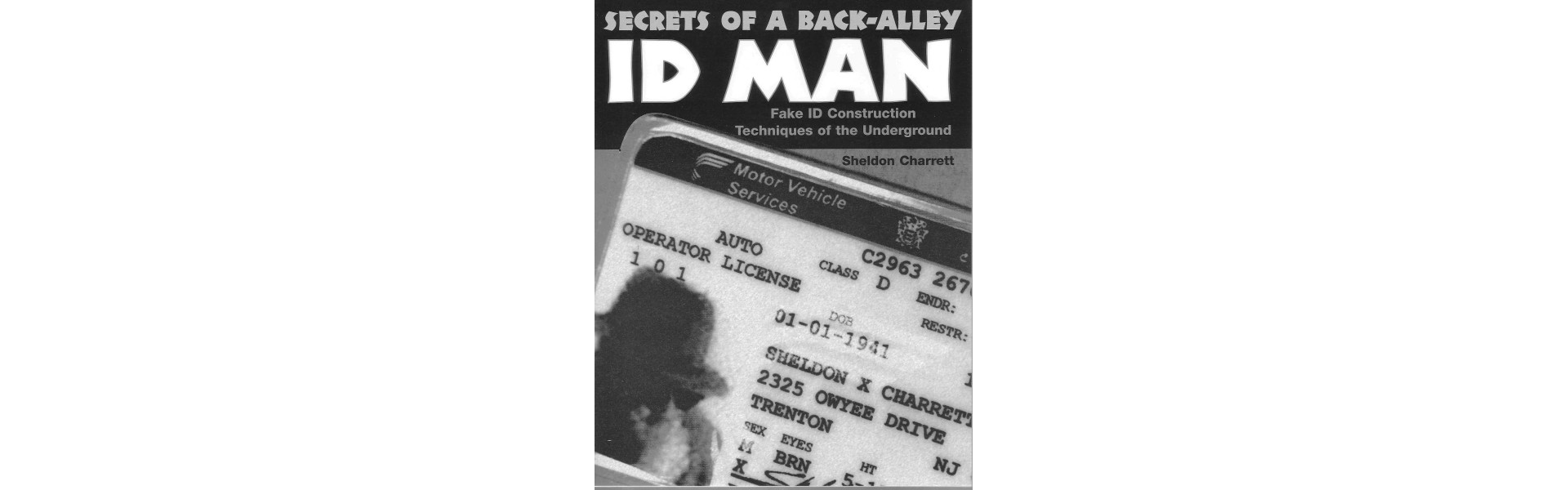

In this candid retrospective, the author presents a behind-the-scenes look at older methods once used by underground craftsmen to manufacture counterfeit identification. Written as a first-person account of an enigmatic “privacy advocate,” the book chronicles both rudimentary tricks of the trade and more sophisticated experiments, always stressing the resourcefulness of individuals working under the radar.

At its core, this volume reads like a historic exploration of a niche skill set. Its opening chapters discuss the motivations for forging documents in bygone eras—ranging from privacy concerns to more opportunistic reasons—and underline how these pressing desires led people to improvise with whatever technology was at hand. From there, the text delves into two main modes of operation, contrasting the “old school” with the “new school.” Charrett’s expertise is evident from his other works, such as "Electronic Circuits" and "Secrets of an Old-Fashioned Spy Identity," suggesting a deep understanding of both technical and covert practices.

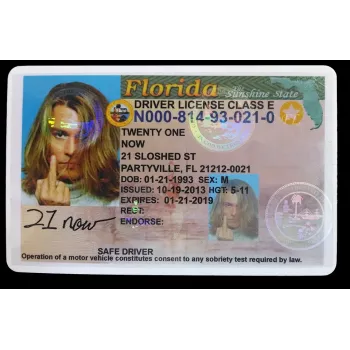

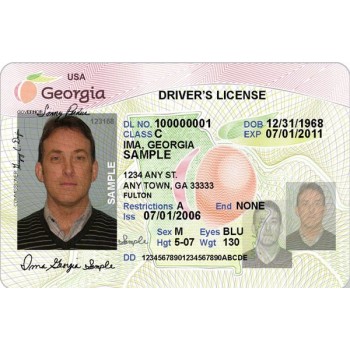

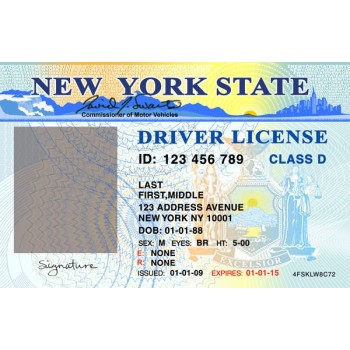

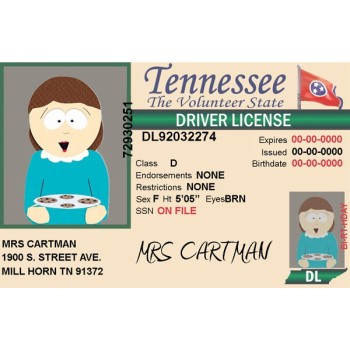

The first mode—“old school”—relies on manual, photographic, and film-based strategies. Readers learn how basic equipment such as single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras, typewriters, and hot lamination machines formed the backbone of mid-to-late 20th-century forgeries. The resourcefulness on display is remarkable: forging seals using offbeat materials, manipulating photographs by cutting and re-shooting images, and assembling rudimentary holographic layers well before the digital era.

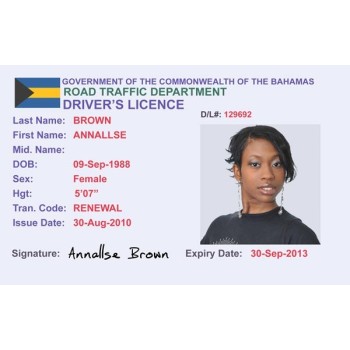

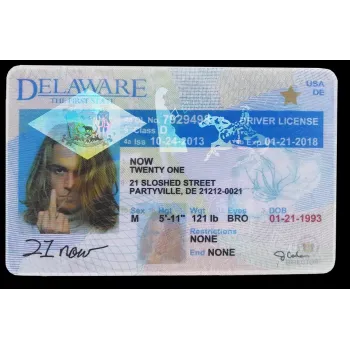

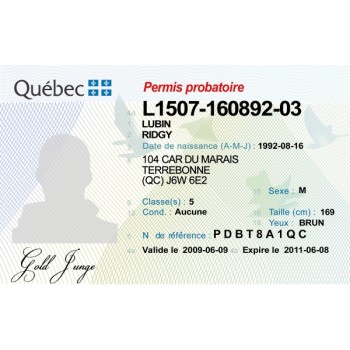

The second mode—“new school”—demonstrates how once-novel home computing and printing methods changed everything. Here, one sees how even outdated scanners and inkjet printers—long obsolete by modern standards—revolutionized the production process when they first appeared. The text touches upon basic image editing to incorporate personal photos and digital overlays, as well as the struggle to replicate “secure” design elements. There is an almost improvisational feel to these segments, as the author experiments with different papers, printers, and laminates to figure out what might fool unwary eyes.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect is the emphasis on inventive solutions to each new obstacle. When lamination pouches created annoying air bubbles or blurred ink over the years, the forgers simply toyed with cold lamination sheets or layered transparency films in new ways. When holographic emblems became the norm for official documents, the author investigated budget-friendly workarounds: diffraction films, “rainbow” overlays, and even homemade stamping methods mimicking embossed seals.

In many ways, the book offers an insight into a subculture that combined artisan flair with a trial-and-error ethos. Its descriptive tone reveals an odd mixture of pride and frustration: pride in the ingenuity needed to circumvent ever-evolving security features, frustration at the constant upgrades by government and corporate entities trying to stay one step ahead.

As a “book review,” this work stands out for its unfiltered approach to a clandestine craft. While explicitly disavowing criminal activity, it provides a lens into how certain individuals once refused to let bureaucracies pigeonhole their identities. The real draw for history-minded readers is witnessing the shift from basic photographic splicing, lamination, and typewritten details to the more elaborate manipulations possible through desktop publishing. What emerges is a testament to the adaptability of those who, rightly or wrongly, chose to live behind assumed names and improvised documents.

Overall, this study offers a rare window into the unconventional techniques people devised in an era when professional-grade equipment was generally off-limits. It is neither a technical manual nor a moral treatise; rather, it’s best approached as a historical curiosity—one that examines the wily, persistent methods developed by unorthodox artisans seeking to stay one step ahead of the status quo.